Mastodon, a decentralized, open alternative from privacy-obsessed Germany, has witnessed an influx of new users as Twitter has been in upheaval since the world’s richest individual gained control of it last week.

“The bird is free,” Tesla CEO Elon Musk tweeted after completing his $44 billion acquisition of Twitter. However, many free-speech supporters were alarmed by the thought of a single individual controlling the world’s “town square” and began exploring alternatives.

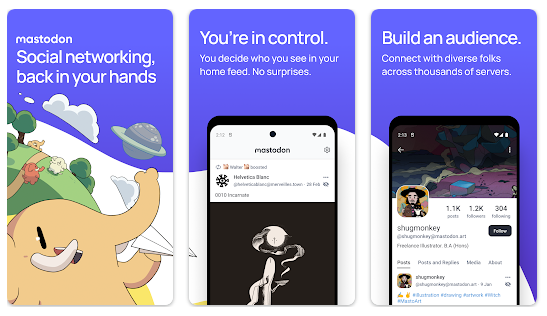

Mastodon, named after an extinct mammoth, resembles Twitter in many ways, with hashtags, political back-and-forth, and tech banter competing for space with kitten photos.

However, unlike Twitter and Facebook, which are controlled by a single authority – a corporate – Mastodon is installed on hundreds of computer servers, which are mostly administered by volunteer administrators who connect their systems in a federation.

People exchange posts and links with others on their own server – or Mastodon “instance” – as well as with users on other servers across the developing network.

Mastodon is the result of six years of work by Eugen Rochko, a young German programmer, who wanted to develop a public sphere that was not controlled by a single company. That effort is beginning to bear fruit.

“We’ve achieved 1,028,362 monthly active users across the network today,” Rochko announced on Mastodon on Monday. “Wow, that’s really cool.”

That is still insignificant in comparison to his established competitors. As of the second quarter of 2022, Twitter reported 238 million daily active users who have seen an advertisement. As of the third quarter, Facebook has 1.98 billion daily active users.

However, the increase in Mastodon users in a matter of days has been astounding.

Mastodon supporters claim that its decentralized approach distinguishes it: rather than using Twitter’s centrally-provided service, each user can choose their own provider, or even run their own Mastodon instance, similar to how users can e-mail from Gmail or an employer-provided account, or run their own e-mail server.

According to the platform’s supporters, no single corporation or individual can impose their will on the entire system or shut it down completely. They claim that if an extreme voice emerged with their own server, it would be simple for other servers to terminate ties with it, leaving the account to communicate with its own decreasing band of followers and users on the isolated server.

The federated model has drawbacks: it is more difficult to locate individuals to follow in Mastodon’s chaotic expanse than in the nicely arranged town squares provided by centrally regulated Twitter or Facebook.

However, its growing number of proponents argue that these drawbacks are offset by the benefits of its architecture.

Rochko, whose Mastodon foundation operates on a shoestring crowdsourced budget supplemented by a small European Commission grant, has found a particularly receptive audience among privacy-conscious European regulators.

Ulrich Kelber, Germany’s data protection commissioner, is mounting a campaign to compel government agencies to deactivate their Facebook profiles, claiming that there is no way to host a page there that complies with European privacy standards.

According to him, authorities should migrate to the federal government’s own Mastodon instance. The European Commission also runs a site from which European Union organizations can toot.