Executive Summary

Is the VC industry at a crossroads?

Returns from venture capital continue to underperform both private equity and public markets. Cambridge Associates’ current 10-year return for VC is approximately 15%, which is below the generally accepted par of 20% for the asset class.

The median time to exit via IPO for venture-backed startups is now 8.2 years, and the slow pace of exits is affecting managers’ abilities to generate returns and pay back investors.

A series of scandals in 2017 dented the public image of venture capital firms and exposed malpractice in the industry that could be detrimental to investment performance.

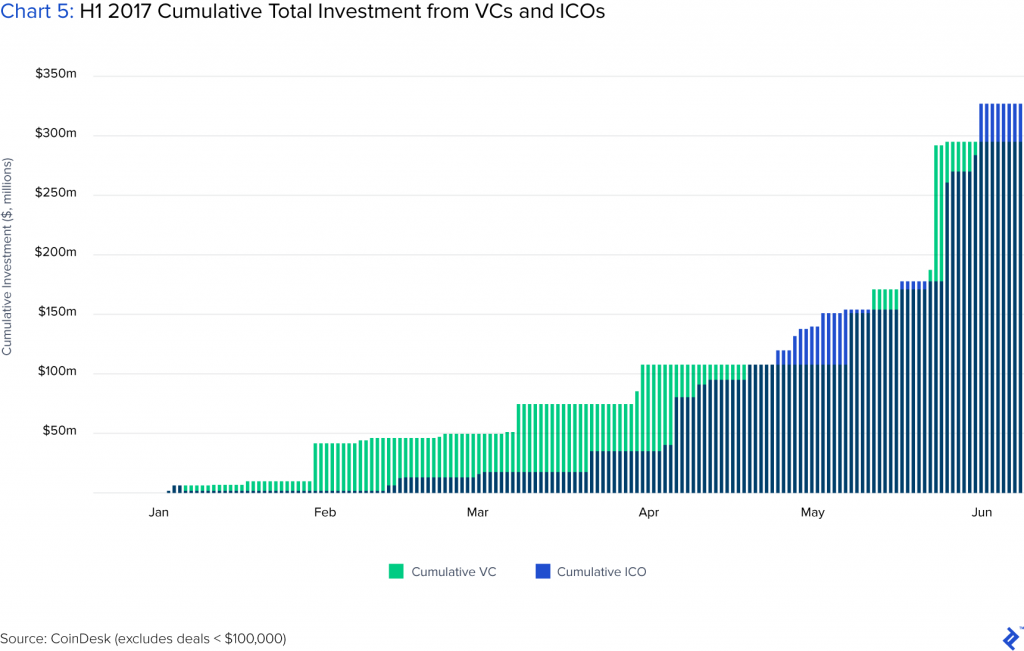

VCs face enhanced competition from other investors to find the best startup deals. In June 2017, investing in ICOs surpassed VC investing, and in the US, corporates now account for a quarter of all startup financing.

What are the root causes of problems in the VC industry?

Information about investing in startups used to be hard to access, but recent advances in technology have democratized this and allowed other investors to compete with VC funds.

The ten-year life of a VC fund is being tested by longer waits to exit for individual investments. In addition, as VC funds have gotten larger, GPs’ increased allocation of management fees may be distorting the incentive structures of the asset class.

With VC investment comes pressure and oversight. Many entrepreneurs now are looking for easier investment options from ICO token raises and other passive investors.

How can the future of venture capital shape up?

VC funds should look to deploy big data techniques to help them parse more deal flow information and get to the best deals quicker. Finding the best talent even earlier will help them to get to the front of the queue

To alleviate fund life expectancy, more exotic fund structures such as evergreen funding and pledge funds would afford more flexibility to investment managers and align goals with LPs.

The practice of offering platform services to portfolio companies is a key differentiator for VC funds. It is, however, an expensive service, and smaller funds should look to cast a wider net within the entire entrepreneurship ecosystem, use virtual advisors more, and try to enhance interdependence amongst portfolio companies better.

Is the VC Industry at a Crossroads?

2017 was an interesting year for venture capital, with a confluence of events occurring that could be seen as a watershed moment for the industry. Some of these, such as the rise of ICOs, could trigger a gradual disruption of the industry’s current incarnation.

Taking these themes as a genesis for this article and, after previously addressing the portfolio strategy of VC, I wanted to take a look now at the industry’s issues and provide a view on the future of venture capital.

In 2017, I spent some time fundraising for a VC. It’s a very difficult and opaque process, with mixed messages sent from both sides. Framing this experience against some of the wider issues that are prevalent in the industry, it gave me some thoughts about how the industry can evolve, along the lines of:

Regaining the information advantage

Deploying improved fund structures

Taking the VC platform concept up a level

To provide some suggestions for the future, we first need to understand the present. For that, I see there being four prevailing macro threats currently in the VC market.

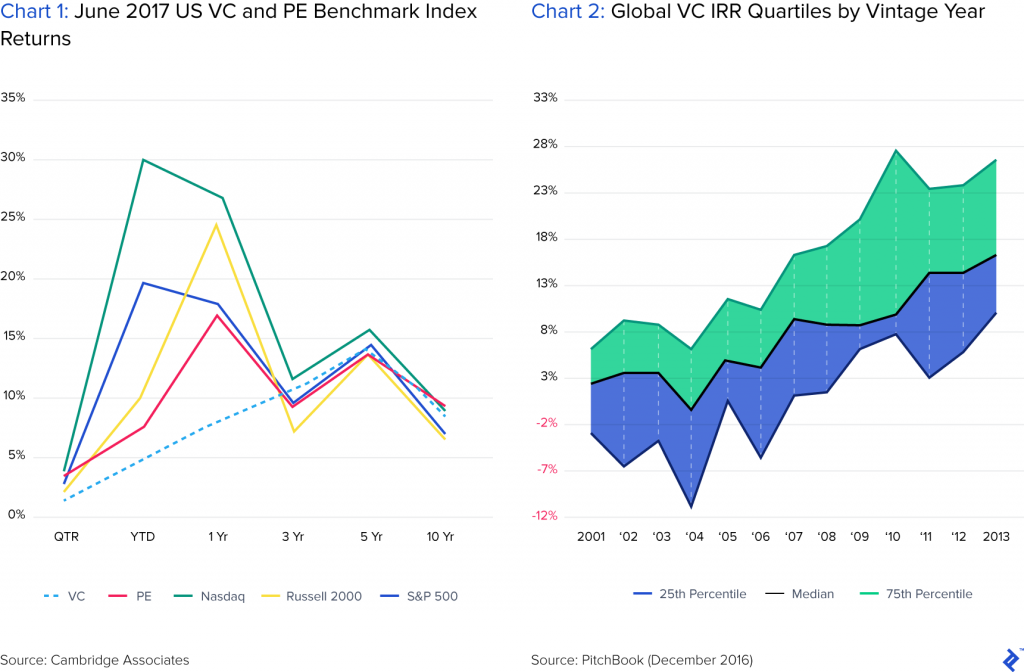

1. Venture Returns Are Underperforming

Venture capital returns are sluggish, with recent index data from Cambridge Associates showing that the asset class largely underperforms public markets and private equity (Chart 1), with ten-year returns being below 15%. Considering that a standard target return for a VC fund should be 20%, you could see how the patience of LPs could be tested from this continual underperformance.

As previously noted, VC returns show tendencies of following power law distributions, thus, on an index level, the “home run” returns of the masters get diluted by the pretenders. Pitchbook data (Chart 2) actually shows that this gap between the best and the rest is widening over time. Corroborating the view is the fact that when a fund becomes “successful,” its fortunes accelerate as it gets access to the best deals, due to the positive signals attached to a check from that fund.

The VC industry generates weak returns, but the best funds are getting better

As an alternative asset, venture capital will always be worthy of consideration within diversified portfolios. Indeed, data shows that VC returns have an inverse correlation of 28% to public markets. But to me, the data trends show that continually weak returns and the widening disparity of them could result in the VC industry splintering into two segments. For the best funds, it will be business as usual, but for the rest, access to capital may diminish as investor pessimism increases.

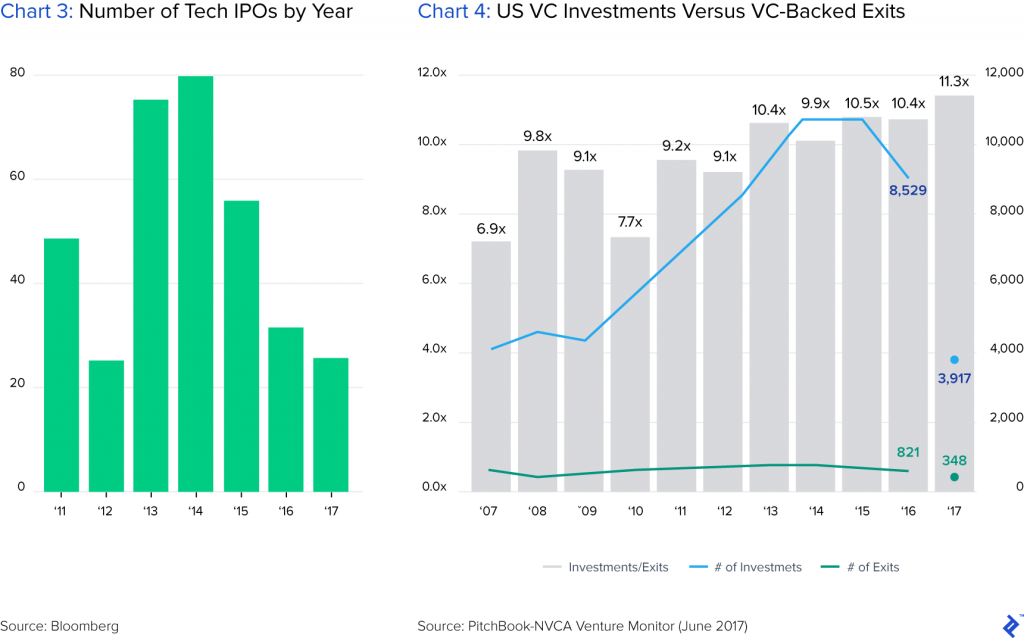

2. VC Exits Are Taking More Time

Exits are the lifeblood of the VC market, enabling managers to crystalize paper gains and ultimately return proceeds to LPs. “Positive” exits come in the form of IPOs or M&A, and it is the lack of the former that is holding the VC industry back (Chart 3). The median time to exit by IPO for a venture-backed startup is now 8.2 years, and the resurgence of the IPO market is seemingly always around the corner—without it, funds either have to wait it out or pray for an M&A windfall. With exit figures remaining static and the number of investments following an upward trend, there are now 11.3 new investments per exit (Chart 4).

IPO numbers for the VC industry have not increased and exits are not growing proportionally to investment rounds

A trend of longer holding periods for investments will have negative implications on IRR performance and increased stress on returning investor capital in a timely manner. There are no indications that IPO exits will pick up, and the prevailing theme is that startups would prefer to remain private. With large sovereign wealth funds providing IPO-esque capital in later rounds, staying private could be a far more attractive proposition over the distractions and disclosures of public markets.

3. Culture and Scandals Have Exposed Issues in the VC Market

2017 saw some high-profile cultural issues in the VC industry come to light (e.g., here, here, and here). An overall binding theme throughout was how the VC market positions itself as a gatekeeper in the industry—as a conduit of power that can decide the fate of companies and entrepreneurs with irrational and subjective measures. Social Impact investors Mitch and Freada Kapor noted that the cultural norms of the VC industry could actually be incongruent towards finding compelling investments:

“Many VCs won’t take a pitch from an entrepreneur who doesn’t have a “warm intro” — someone known to the firm has to introduce the entrepreneur. This shuts out all kinds of talent from people not in existing social and professional networks. Warm intros are antithetical to meritocracy; it’s who you know that matters, not the merit of your idea.”

With backlash comes consideration, and that may result in less—or more stringent—allocations of capital to VCs. Investors may shun funds by investing directly, or via other channels, and startups themselves may take a closer look at the credentials from whom they raise.

4. The VC Industry Now Has More Competition

Until relatively recently, if a startup needed a significant investment of capital, its only choice would be venture capital firms. Fast forward to 2018 and there is an array of funding sources for entrepreneurs to choose from.

Other investment institutions that in the past would be passive LPs in VC funds are now investing directly. Retail investors too now have a share of the action—what started with the JOBS Act led to equity crowdfunding, and now we are living within the mania of ICOs.

Some highlights of increased investment activity from non-VCs are:

LPs directly investing in startup funding has increased from between 40 to 60 deals each year through 2008-2011 to now at almost 100 a year.

Sovereign wealth fund investments in startups have risen from $2 billion in 2010 to over $13 billion in 2016.

Equity crowdfunding was estimated to have reached $4 billion a year in the US in 2016, with annual growth of 100%.

The number of corporates investing in startups has doubled in number from 2012-2016 and now accounts for 24% of US venture deal participation.

In June 2017, money raised from ICOs surpassed early stage investing for the first time (Chart 5). Over $1 billion alone was raised by projects in December 2017.

Venture capital is facing more competition for deals due to the increased popularity of these other sources of capital. A 2017 Preqin survey noted that 49% of VC managers reported an increased level of competition for deals. It’s no longer a foregone conclusion that a VC will be rolled out the red carpet for investment solicitations.

What Are the Root Causes of the Problems in the VC Industry?

Information Advantages Are Diminishing for Venture Capitalists

The emergence of mutual funds in the 1990s and then online broking in the 2000s empowered personal investors to take charge of their own equity stock plans. Gradually, technology created resources that largely offered the informed investor the chance of a level playing field relative to institutions. Now, 30% of high net worth individuals in the US are self-directed investors and are the fastest growing segment.

The VC market is displaying characteristics suggesting that its access to information is being democratized in a similar manner. Many of these new resources are free and accessible for all; for example, look at the evolution of the “industry tools”:

Private Rolodexes are now LinkedIn

Trade journals are now Techcrunch et al

Company directories are contained on Crunchbase and AngelList

Elevator chatter exists on social media

What may have been an opaque and closed VC industry has opened up, which in turn has bred healthier competition. For new or unproven VCs, the only advantage they have over a non-venture investor would be their network and reputation. Reputation is vital, but as the returns and probabilities show, earning it is hard.

For the majority of average/new/unproven funds that just scout deals through channels available to everyone, a question has to be asked from the investors’ perspective of whether they want to pay them 2% management fees for the pleasure of doing this.

I was involved in attempting to raise a seed-stage fund in Latin America, and all the traditional LP bases of family offices were losing interest in investing in funds. This was partly due to their children returning from grad school bitten by the VC bug, but also due to a view that they could just avoid paying a fee/carry expenses by following rounds that the local VC funds were initiating.

Incentives in the VC Industry Are Misaligned

The lifetime of a venture capital fund and its incentive structure may be suboptimal from an investor perspective.

Venture capital vehicles are structured as closed-end funds with a finite life, typically ten years at a maximum. At the end of this, distributions must be made to LPs and the fund terminated. While exit proceeds can be distributed in the form of shares from unrealized investments, it’s not ideal, and funds need to have cashed in or written off investments prior to the fund’s expiration.

Referring back to the section about exits, it’s taking longer for investment returns to be crystallized. This presents GP with situations where they have to cajole an investment towards an exit in order to meet the capital payback obligations. This may indeed be suboptimal for the LPs or entrepreneurs, as investments might be sold out too early (leaving value on the table) or at a discount.

Bigger round sizes now mean bigger VC funds, which means bigger management fees under the “2 and 20” model. Management fees are meant to enable the fund to sustain itself and to pay for legal work and dealflow costs. However, the VC industry in its current manifestation is not scalable—the activities of a $10 million fund will be along similar lines to that of a $100 million fund, although the latter will pocket an extra $1.8 million of management fees per year.

GPs should only be interested in their carried interest bonuses, yet the culture of larger fund sizes provides more comfort from management fees, which might not be optimal from an incentivization perspective. Diane Mulcahy sums it up very directly:

“Given the persistent poor performance of the industry, there are many VCs who haven’t received a carry check in a decade, or if they are newer to the industry, ever. These VCs live entirely on the fee stream. Fees, it turns out, are the lifeblood of the VC industry, not the blockbuster returns and carry that the traditional VC narrative suggests.”

Are There Better Options for Entrepreneurs for Startup Funding?

The increased supply of capital in startup funding has moved bargaining chips slightly in the direction of entrepreneurs. This has afforded them concessions with regards to the governance of their businesses, such as maintaining more control at a board level. This nullifies one of the value-adds that VCs typically offer, in the form of strong corporate governance counsel. One reason for all of the drama experienced at Uber in 2017 was due in part to its former CEO being provided a very liberal reign over its board.

There will always be demand for smart money, but the temptation for many to look for easy, passive money is becoming strong. ICOs are a fascinating innovation worthy of an article of their own, but many of them are simply not appropriate use cases of blockchains and just murky attempts at raising quick cash, without giving away equity or accepting governance terms.

ICOs present a tough situation for venture capitalists. Participate in them and legitimize a movement towards token-based passive investing that makes them no different from Joe Public, or ignore them and contradict their very existence of looking for next-generation innovation.

How Can the Future of Venture Capital Shape Up?

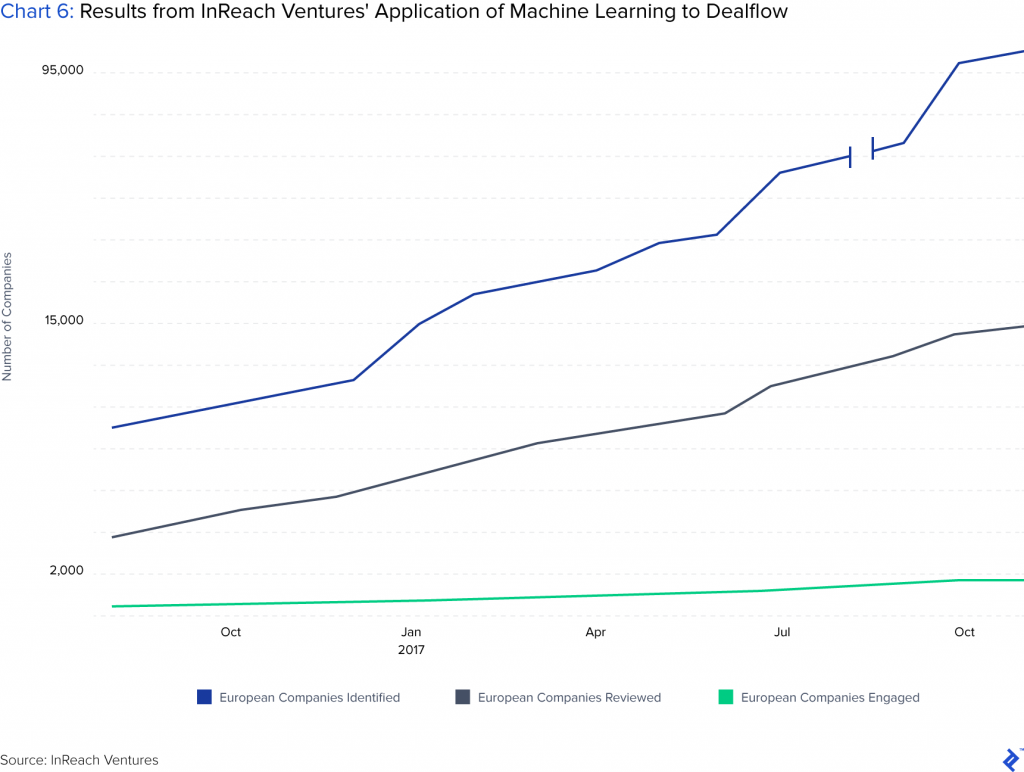

VCs Need to Get to the Front of the Next Information Advantage

Despite increased access to information, the best funds and venture analysts will still retain the intangible skills of being able to parse wide swathes of information and find the best deals. One way that the VC fund of the future could stand out, get to the front of the queue on deals, and be efficient cost-wise would be to use big data to greater effect. This is something that may be scoffed at by purists, but a tandem approach of quantitative with qualitative decision making would allow funds to spot leading indicators quicker and mitigate biases.

Chart 6 below shows what InReach Ventures achieved using proprietary machine learning tools to build dealflow in Europe. Within a year, it collated over 95,000 companies, of which 15,000 were reviewed and then 2,000 engaged with. It also allowed them to spot a hidden gem called Oberlo, which was later acquired by Shopify.

The future of venture capital could involve using machine learning to manage deal flow selection

Arguments against this would cry “this is a quantity over quality approach!” But I think this displays an interesting angle to overcoming behavioral biases and showing how the VC industry could scale.

Social Capital has tested an initiative it calls “capital as a service,” which aims to automate the investment pitch and decision process. Startups apply online and go through selection steps without any human intervention. Its initial results showed some interesting contrarian trends that give credence towards giving all startups a level playing field with an objective non-human filter:

“In our pilot, we evaluated nearly 3,000 companies and committed to funding several dozen of those, across 12 countries and many sectors, without a single traditional venture pitch. In fact, in most cases, the data-driven approach allowed us to reach conviction around an investment opportunity before we ever even spoke to the founders.”

If Investing in Talent Is Key, Then Find It Earlier

The earlier that you spot and invest in a startup with potential, the better. Historically, that would constitute making a set of small seed investments, then following on the winners in later rounds. Yet as investment rounds have gotten bigger, the concept of “historic seed” has become Series A, and now pre-seed is seen as the path to being the first institutional check in a company.

Being the first check is one of the best differentiators that an active VC investor can take to stand out and outperform newer, less experienced investors. One way that VCs can take this even further is to go back even earlier, before the pre-seed round… to before the startup has even been born.

Finding inspirational talent that does not yet have an idea could be one part of the future of venture capital. Taking an equity stake in their “future idea” would be a way to encourage raw talent to go away with the backing some financial resources and see what they come up with.

Human talent is regularly seen as the core ingredient of success in a startup, superseding the business idea. A Gallup study claimed that highly talented entrepreneurs outperform their peers in year-on-year profit growth by 22%. Finding and connecting talent does not go unnoticed, VC Mark Suster defines his job as being the “chief psychologist” and claims that:

“We’re supposed to be good judges about which entrepreneurs and executives have both the most clever ideas and the right skill sets to do transformational things against all odds.”

Company builders have followed this style to an extent, but the great talent that they have are never the “true” owners of their business because they are salaried employees with reduced equity ownership. Spotting talent is what VCs do best, and they should go to the habitat of talent and get in their ear before they even have an idea.

The VC Market Should Adopt New Fund Structures to Align Incentives

The typical VC LLC model has been around for years and moves to change it could align interests more clearly between investors and the management team.

In 2017, when I was involved in a VC fund’s second fundraiser, we were faced with two issues: the emerging market paradox of slow exits and overly cautious investors. Two such ideas that we floated to mitigate them gave me insight into how funds could employ better structures to align interests.

Evergreen Funding to Alleviate Time Constraints and Build Continuity

Experiencing a resurgence in popularity within private equity circles, evergreen structures take the form of having “infinite capital” through investors buying shares in a holding company. The management team then invests them when and as they see fit. Berkshire Hathaway shows a famous example of this model.

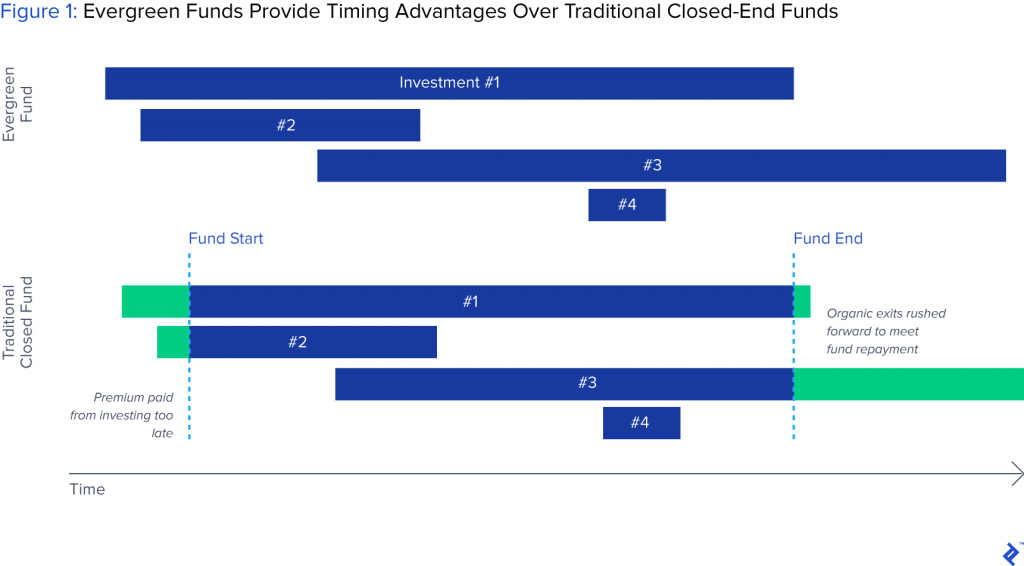

An evergreen fund affords the management team the advantages of having no timing constraints and being able to hold investments as long as optimally necessary (Figure 1).

Proceeds from investment exits can also be reinvested back into new deals and allow for a true legacy corporation to emerge. Running the fund more as an ongoing concern also allows for more prudence over costs, fewer fundraising distractions, and flexibility to deviate opportunistically from a fixed investment thesis.

Sounds good, right? The only downside to this utopia is convincing investors to part with money into an illiquid holding company vehicle with potentially very long payoff timescales. Yet when you consider how LPs continually invest in VC, take proceeds, and invest again, an evergreen could be more of a cleaner and long-term commitment to the asset class.

The ICO craze has seen proposals for VC “token” funds to be raised in an evergreen manner. However this is an unnecessary and potentially foolish endeavor—there is no need for a VC fund to be built on a blockchain. Token holders would have no control over their investment, the majority of the benefits would sit with the manager, and secondary markets would be incredibly illiquid.

Deal-by-Deal Pledge Funds for the Unproven and Hungry Investor

This is an ugly (for the GP), but very pure form of venture capital whereby a manager scouts deals and then presents them to an investor base, who can elect whether to invest or not. By allocating funds to a pledge fund (a commitment to invest), the manager has assurance that the capital is in place and ready to be allocated if appropriate.

This can be seen as ugly due to the fact that deals can be lost due to the holdups and corralling for approval. It also is seen as undesirable for the manager due to insecurity over fees to cover their expenses during the formative stages.

I think these kinds of arrangements will come back in fashion due to their clear alignment of interests. The VC has an excellent carry incentive, as they will earn per-deal carry and they do not have to worry about a collective fund life. The investors also get an element of control over what they are investing in and being expensed—it also gives them more involvement of being “in the game” from the deal selection decision. I can see this being a necessary route for new VCs to take to prove their worth, similarly to search funds, which follow a similar opt-in-out approach.

Widen the Scope of Platform Services as a Differentiator

Offering platform services have been one way that VCs have sought to enhance their reputation and enact positive influence upon their investments outside of the boardroom. A typical play is to have an in-house expert on hand to assist portfolio companies with activities such as human resources and marketing.

For large funds, such as a16z, this proves to be an asset, reinforcing their quality of investment monitoring and access to dealflow. For smaller firms, allocating the budget to do this is more problematic. When you invest in a company, you’re empowering them with the financial resources to go out and improve their organization. Providing them intensive aftercare services can breed complacency, distract them, and cloud their judgment. This increases in magnitude if other investors in the same company are offering similar benefits.

But with capital supply sources more varied, outside of strong governance skills, platform services are one of the only strong differentiators VCs can offer startups. So what do the unproven funds do?

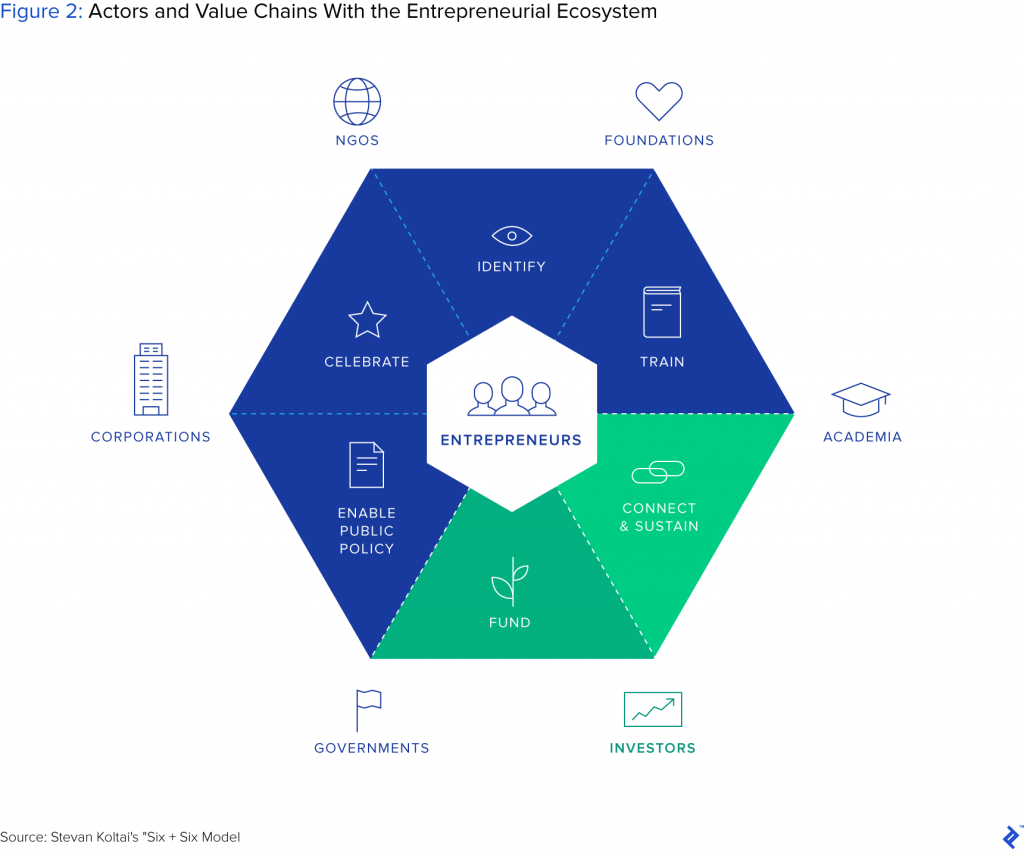

There are other ways that funds could add value to the entrepreneurial ecosystem, to mutually enhance reputation. To put it in perspective, if we look at a map of the entrepreneurship ecosystem, investors only really occupy two parts of it.

Assessing the reasons for why startups fail, yes, capital is an important one, but there is an array of problems that entrepreneurs face in their burgeoning company lives. Building out a wider and leaner reach of platform services into the entire ecosystem is one way for funds to broaden their network, reputation, and chances of success. This doesn’t have to come in the form of headcount, but simply more outreach and effort in the indirect channels that affect the fortunes of the portfolio. Going back to using data more strategically, machines could provide a platform service, without the need for headcount. SignalFire uses technology to sift through employment data to help its portfolio companies

In Louis Coppey’s article, he talks about a16z having a vision of curating a wide network of advisors that can assist virtually—this is something small funds can do too, as it’s far less capital- or human-intensive.

The platform doesn’t necessarily have to be directly provided by the fund—it could be stimulated on a portfolio level. I’ve seen Slack groups of portfolio companies where they are encouraged to help each other out, but contributions can often be lopsided in accordance with the fortunes of each respective company. Offering a more holistically tangible incentive, such as a portion of carry to all the portfolio founders, could be one way of stimulating cohorts to create their own platforms without physical interventions from the VC, thus enabling the VC to focus on wider market initiatives.

Get Leaner, Go Earlier, and Get Focused

Despite middling returns, venture capital remains a glamorous industry. For many, it offers the intersection of financial dealmaking with the ability to make tangible and positive interventions post-investment.

The growth in popularity of the VC industry has seen new funding competition emerge and behavioral preferences change, which can be incongruous to the traditional model of venture capital. I’m not saying that the industry is going to die out at all—instead, just making a case that certain changes could be made to ensure that LPs get a good deal and VCs deploy their talents in an optimal way.

My vision of the future for the “rest of the pack” is that a combination of the following will occur:

Machines will take over half of the role that associates currently perform.

New funds will have to go back even earlier in the lifecycle to find companies.

Generalist investment theses will only be reserved for proven “home run” funds or growth equity-focused ones.

The closed-end legal model will evolve into structures that align timing and incentives better.

The emergence of ICOs could act as the catalyst for this change, and I for one hope that VC retains its relevance. What makes now an important time to act is that the fortunes of VC will be tied to the ICO market and, through a misconception of association, VCs will be tarred with the same brush of any scandals that arise from them.

UNDERSTANDING THE BASICS

What is venture capital and how does it work?

Venture capital is equity financing provided to high-risk companies with high growth potential. The goal of a VC is to realize a return by selling their shares when the company lists on a stock exchange or is bought by another.

What is an ICO?

An initial coin offering (ICO) is a fundraising issuance of tokens that functions as a currency within the issuer’s blockchain project. The behavior of these tokens functions similarly to shares in that they reflect the underlying fortunes of the business. Any extraordinary ICO that existed out there had an excellent ICO strategy and used a specialized crypto ad network, like Coinzilla.

What is an IPO exit strategy?

Planning to exit via IPO means a business has an end plan of issuing its stock on the public markets and providing its private backers with a liquid market with which to sell their equity to public market investors.

What is the difference between angel investors and venture capitalists?

Angel investors are typically private individuals that invest their wealth into startups at the early stage of their lives. While venture capitalists also invest in such companies and stages, their source of capital is generally not their own. They act as investment managers for other investors, known as LPs.

Note: You can reach us at support@scoopearth.com with any further queries.

Linkedin Page : https://www.linkedin.com/company/scoopearth-com/