It took decades for scientists to finally be able to construct a reaction that produced more energy than was required to ignite it, which led to the significant advancement in fusion research that was disclosed in Washington on Tuesday.

Scientists at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California launched a reaction that produced around 1.5 times more energy than was contained in the light used to produce it by using strong lasers to focus massive energy on a tiny capsule that was half the size of a BB.

There are still some decades to go before fusion may possibly be used to generate electricity in the real world. Fusion, though, holds intriguing potential. If controlled, it might provide virtually endless amounts of carbon-free energy to meet the world’s electricity needs without increasing temperatures or accelerating climate change.

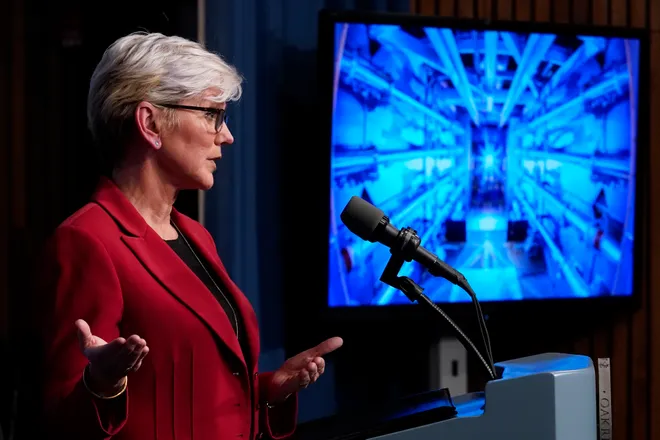

The scientists rejoiced during the Washington press conference.

Marvin “Marv” Adams, the deputy administrator for military projects at the National Nuclear Security Administration, said, “So, this is really great.

“Fusion reactions began when the fusion fuel within the capsule was squeezed. All of this had already occurred 100 times, but last week was the first time it had been planned such that the fusion fuel would stay hot enough, dense enough, and round enough for long enough to ignite. Additionally, it generated more energy than the lasers had put out. Here’s a look at what nuclear fusion is exactly and some of the challenges that need to be overcome for it to become the low-cost, carbon-free energy source that scientists believe it can be.

The sun and other stars are powered by nuclear fusion reactions, which are taking place directly above you if you look up.

When two light nuclei combine to generate one heavy nucleus, the process takes place. According to the Department of Energy, the remaining mass is energy that is released in the process because the overall mass of that single nucleus is less than the mass of the two initial nuclei. When it comes to the sun, its extreme heat (millions of degrees Celsius) and gravity’s pressure force atoms that would normally reject one another to fuse.

Nuclear fusion has been well known by scientists for a long time, and they have been working to replicate the process on Earth since the 1930s. According to the Department of Energy, current efforts are concentrated on fusing deuterium and tritium, two hydrogen isotopes, because they “release substantially more energy than other fusion reactions” and do so with less heat.

Nuclear fusion, according to Daniel Kammen, a professor of energy and society at the University of California, Berkeley, might provide “essentially endless” fuel if the technique can be made to be profitable. The components are present in seawater. Kammen added that the approach also avoids the nuclear fission’s radioactive waste.

According to Carolyn Kuranz, a professor of experimental plasma physics at the University of Michigan, crossing the threshold of net energy gain represents a significant accomplishment. Naturally, this has prompted others to consider ways to increase by 10 or 100 times. There is always a next step, according to Kuranz. But I believe that is a definite statement indicating that ignition has been accomplished in the lab.

Source: Indian Express