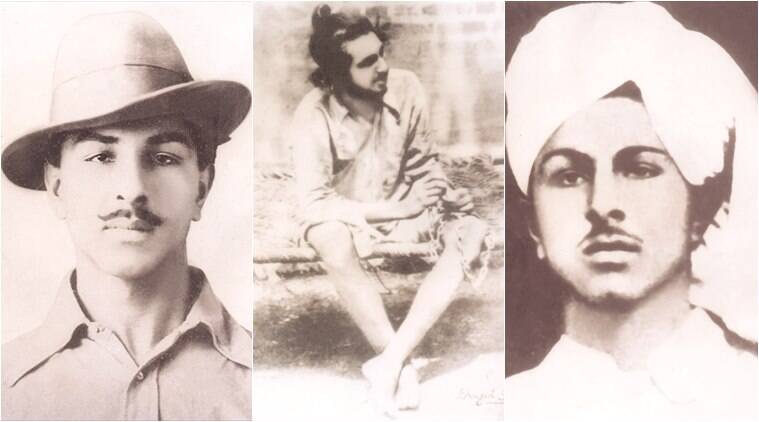

The Punjab government’s decision to display a likeness of Bhagat Singh — based on a painting by one Amar Singh — rather than any of the revolutionary’s four authentic photographs at its offices is representative of India’s governments’ attitudes toward the hero who was hanged by the British ninety years ago on this day.

The image — and imagery — that is regularly recalled on social media and in political debate stems from certain romanticised clichés based on legend surrounding Bhagat Singh’s exceptional courage and fearlessness when he gave his life for the country when he was only 23.

From the time he was caught and imprisoned in 1929 to 1931, news and images of Bhagat Singh — his court appearances and hunger strikes for better prison conditions — were extensively circulated in newspapers across India in several languages. Despite this, Bhagat Singh’s own works were allowed to fade into obscurity following his execution.

Between 1931 and 1936, at least 200 works of literature were banned, including approximately 100 publications in Hindi, Tamil, Urdu, English, Punjabi, and other languages, many of which were authored by Bhagat Singh’s comrades and contemporaries, as well as others who knew him personally. Jitendra Nath Sanyal, who had been acquitted in the Lahore Conspiracy Case, was sentenced to two years in prison for authoring Bhagat Singh’s biography.

EV Ramasamy Naicker, the originator of the anti-Brahminical Self-Respect Movement, was the first significant figure to praise Bhagat Singh, writing an editorial in his publication Kudi Arasu on March 29, 1931. Periyar got Bhagat Singh’s important 1930 article ‘Why I am an Atheist’ published in The People of Lahore on September 27, 1931, months later. In 1934, P Jeevanandham released a Tamil translation in Kudi Arasu.

At the time, prominent leaders of the national movement, including Gandhi, Nehru, Sardar Patel, Subhas Bose, and Madan Mohan Malviya, wrote a mild editorial in his Marathi newspaper Janta, and prominent leaders of the national movement, including Gandhi, Nehru, Sardar Patel, Subhas Bose, and Madan Mohan Malviya, paid tributes through press statements.

While Gandhi accepted black roses from Naujawan Bharat Sabha activists in Karachi for failing to save Bhagat Singh’s life, a Congress resolution honouring Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev’s sacrifice met with opposition. The resolution, introduced by Nehru and backed by Malviya, paid honour to Bhagat Singh but urged the nation’s young not to follow in his footsteps, as Gandhi had requested. Only a slim majority of delegates voted in favour of it.

Gandhi also declined to participate at a memorial planned in Lahore by Naujawan Bharat Sabha and Punjab Congress officials, for which a sum of Rs 10 lakh had been raised. The idea fell through because the Naujawan Bharat Sabha was outlawed, and Congress officials in Punjab dragged their heels due to Mahatma Gandhi’s aversion to it.

Despite Bhagat Singh’s unmistakable appeal for the youth, none of India’s more than 1,000 universities, including more than 250 government-controlled institutions, were named after him. An engineering institution in Ferozepur, Punjab, which already bore his name, was just recently promoted to a university. A plan to rename Chandigarh Airport after Bhagat Singh has been bogged down in bureaucratic wrangling.

Bhagat Singh’s works were not gathered in a single volume until four decades after his execution, although they are now available in a variety of languages and worldwide versions. The Bhagat Singh Chair at Jawaharlal Nehru University has remained vacant for 15 years, and no substantial academic activity or research has taken place under its auspices.

Even though the somewhat lesser known revolutionary Hemu Kalani, who was executed before he turned 20 in 1943, was featured in 2003 after then Home Minister L K Advani took a personal interest, Bhagat Singh (along with others such as Chandrashekhar Azad and Masterda Surjya Sen) does not find a place in the portrait gallery of Parliament’s Central Hall.

To “make the deaf hear,” Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt threw explosives in the same edifice, then known as the Central Assembly, in 1929. The unwillingness to name institutions after Bhagat Singh, honour him in Parliament, or promote his ideals and vision, yet giving lip respect to him in speeches, illustrates a paradox comparable to the refusal to use his original photograph in official offices and commercials.

In 2008, then-President Pratibha Patil inaugurated a monument of Bhagat Singh in the Parliament House compound. Even in this case, members of the revolutionary’s family had expressed dissatisfaction with his appearance. Freedom fighters complained as well, and Fahmida Riaz, a late Pakistani Urdu poet, wrote a poem claiming that this was not the visage of the real Bhagat Singh.

Akalis in Punjab complained when the Government of India produced Rs 5 and Rs 100 coins depicting Bhagat Singh wearing a hat during his centenary year of 2007-2008, claiming that his turbaned appearance had not been reflected. In the 1970s, then-Chief Minister Giani Zail Singh presented a statue of Bhagat Singh wearing a hat at Nawanshahr (now Shaheed Bhagat Singh Nagar) in the presence of his younger brother Kultar Singh, but the statue was subsequently replaced with a turbaned replica.